- Home

- Slezkine, Yuri

The House of Government

The House of Government Read online

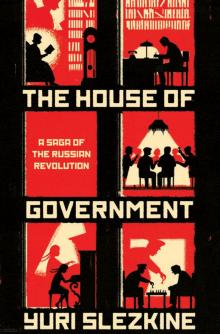

THE HOUSE OF GOVERNMENT

The House of Government.

(Courtesy of the House on the Embankment Museum, Moscow.)

THE HOUSE OF GOVERNMENT

A SAGA OF THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

YURI SLEZKINE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright © 2017 by Yuri Slezkine

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration by Francesco Bongiorni / Marlena Agency

Jacket design by Chris Ferrante

Unless otherwise noted in the caption, all images are courtesy of the House on the Embankment Museum.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Slezkine, Yuri, 1956- author.

Title: The House of Government : a saga of the Russian Revolution / Yuri Slezkine.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016049071 | ISBN 9780691176949 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Moscow (Russia)—Politics and government—20th century. | Communists—Russia (Federation)—Moscow—Biography. | Apartment dwellers—Russia (Federation)—Moscow—Biography. | Victims of state-sponsored terrorism—Russia (Federation)—Moscow—Biography. | Moscow (Russia)—Biography. | Apartment houses—Russia (Federation)—Moscow—History—20th century. | Moscow (Russia)—Buildings, structures, etc. | Political purges—Soviet Union—History. | State-sponsored terrorism—Soviet Union—History. | Soviet Union—Politics and government—1936–1953. | BISAC: HISTORY / Europe / Russia & the Former Soviet Union. | HISTORY / Revolutionary. | HISTORY / Social History. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Ideologies / Communism & Socialism.

Classification: LCC DK601 .S57 2017 | DDC 947.084/10922—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016049071

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Kazimir Text and Kremlin II Pro

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of history. Any resemblance to fictional characters, dead or alive, is entirely coincidental.

Sometimes it seemed to Valène that time had come to a stop, suspended and frozen around an expectation he could not define. The very idea of his projected tableau, whose exposed, fragmented images had begun to haunt every second of his life, furnishing his dreams and ordering his memories; the very idea of this eviscerated building laying bare the cracks of its past and the crumbling of its present; this haphazard piling up of stories grandiose and trivial, frivolous and pathetic, made him think of a grotesque mausoleum erected in memory of companions petrified in terminal poses equally insignificant in their solemnity and banality, as if he had wanted to both prevent and delay these slow or quick deaths that seemed to engulf the entire building, story by story: Monsieur Marcia, Madame Moreau, Madame de Beaumont, Bartlebooth, Rorschash, Mademoiselle Crespi, Madame Albin, Smautf. And him, of course, Valène himself, the house’s oldest inhabitant.

GEORGES PEREC, LIFE: A USER’S MANUAL

Mephisto:

There lies the body; if the soul would fly away,

I shall confront it with the blood-signed scroll.

Alas, they have so many means today

To rob the Devil of a soul.

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE, FAUST,

TRANS. WALTER KAUFMANN

CONTENTS

Preface

XI

Acknowledgments

XVII

BOOK ONE | EN ROUTE

PART I | ANTICIPATION

3

1. The Swamp

5

2. The Preachers

23

3. The Faith

73

PART II | FULFILLMENT

119

4. The Real Day

121

5. The Last Battle

158

6. The New City

180

7. The Great Disappointment

220

8. The Party Line

272

BOOK TWO | AT HOME

PART III | THE SECOND COMING

315

9. The Eternal House

317

10. The New Tenants

377

11. The Economic Foundations

408

12. The Virgin Lands

421

13. The Ideological Substance

454

PART IV | THE REIGN OF THE SAINTS

479

14. The New Life

481

15. The Days Off

508

16. The Houses of Rest

535

17. The Next of Kin

552

18. The Center of the World

582

19. The Pettiness of Existence

610

20. The Thought of Death

623

21. The Happy Childhood

645

22. The New Men

665

BOOK THREE | ON TRIAL

PART V | THE LAST JUDGMENT

697

23. The Telephone Call

699

24. The Admission of Guilt

715

25. The Valley of the Dead

753

26. The Knock on the Door

773

27. The Good People

813

28. The Supreme Penalty

840

PART VI | THE AFTERLIFE

871

29. The End of Childhood

873

30. The Persistence of Happiness

887

31. The Coming of War

912

32. The Return

924

33. The End

946

Epilogue: The House on the Embankment

961

Appendix: Partial List of Leaseholders

983

Notes

995

Index

1083

PREFACE

During the First Five-Year Plan (1928–32), the Soviet government built a new socialist state and a fully nationalized economy. At the same time, it built a house for itself. The House of Government was located in a low-lying area called “the Swamp,” across the Moskva River from the Kremlin. The largest residential building in Europe, it consisted of eleven units of varying heights organized around three interconnected courtyards, each one with its own fountain.

It was conceived as a historic compromise and a structure “of the transitional type.” Halfway between revolutionary avant-garde and socialist realism, it combined clean, straight lines and a transparent design with massive bulk and a solemn neoclassical facade. Halfway between bourgeois individualism and communist collectivism, it combined 505 fully furnished family apartments with public spaces, including a cafeteria, grocery store, walk-in clinic, child-care center, hairdresser’s salon, post office, telegraph, bank, gym, laundry, library, tennis court, and several dozen rooms for various activities (from billiards and target shooting to painting and orchestra rehearsals). Anchoring the ensemble were the State New Theater for 1,300 spectators on the riverfront and the Shock Worker movie thea

ter for 1,500 spectators near the Drainage Canal.

Sharing these facilities, raising their families, employing maids and governesses, and moving from apartment to apartment to keep up with promotions were people’s commissars, deputy commissars, Red Army commanders, Marxist scholars, Gulag officials, industrial managers, foreign communists, socialist-realist writers, record-breaking Stakhanovites (including Aleksei Stakhanov himself) and assorted worthies, including Lenin’s secretary and Stalin’s relatives. (Stalin himself remained across the river in the Kremlin.)

In 1935, the House of Government had 2,655 registered tenants. About 700 of them were state and Party officials assigned to particular apartments; most of the rest were their dependents, including 588 children. Serving the residents and maintaining the building were between six hundred and eight hundred waiters, painters, gardeners, plumbers, janitors, laundresses, floor polishers, and other House of Government employees (including fifty-seven administrators). It was the vanguard’s backyard; a fortress protected by metal gates and armed guards; a dormitory where state officials lived as husbands, wives, parents, and neighbors; a place where revolutionaries came home and the revolution came to die.

In the 1930s and 1940s, about eight hundred House residents and an unspecified number of employees were evicted from their apartments and accused of duplicity, degeneracy, counterrevolutionary activity, or general unreliability. They were all found guilty, one way or another. Three hundred forty-four residents are known to have been shot; the rest were sentenced to various forms of imprisonment. In October 1941, as the Nazis approached Moscow, the remaining residents were evacuated. When they returned, they found many new neighbors, but not many top officials. The House was still there, but it was no longer of Government.

It is still there today, repainted and repopulated. The theater, cinema, and grocery store are in their original locations. One of the apartments is now a museum; the rest are private residencies. Most private residencies contain family archives. The square in front of the building is once again called “Swamp Square.”

■ ■ ■

This book consists of three strains. The first is a family saga involving numerous named and unnamed residents of the House of Government. Readers are urged to think of them as characters in an epic or people in their own lives: some we see and soon forget, some we may or may not recognize (or care to look up), some we are able to identify but do not know much about, and some we know fairly well and are pleased or annoyed to see again. Unlike characters in most epics or people in our own lives, however, no family or individual is indispensable to the story. Only the House of Government is.

The second strain is analytical. Early in the book, the Bolsheviks are identified as millenarian sectarians preparing for the apocalypse. In subsequent chapters, consecutive episodes in the Bolshevik family saga are related to stages in the history of a failed prophecy, from an apparent fulfillment to the great disappointment to a series of postponements to the desperate offer of a last sacrifice. Compared to other sects with similar commitments, the Bolsheviks were remarkable for both their success and their failure. They managed to take over Rome long before their faith could become an inherited habit, but they never figured out how to transform their certainty into a habit that their children or subordinates could inherit.

The third strain is literary. For the Old Bolsheviks, reading the “treasures of world literature” was a crucial part of conversion experiences, courtship rituals, prison “universities,” and House of Government domesticity. For their children, it was the single most important leisure activity and educational requirement. In the chapters that follow, each episode in the Bolshevik family saga and each stage in the history of the Bolshevik prophecy is accompanied by a discussion of the literary works that sought to interpret and mythologize them. Some themes from those works—the flood of revolution, the exodus from slavery, the terror of home life, the rebuilding of the Tower of Babel—are reincorporated into the story of the House of Government. Some literary characters helped to build it, some had apartments there, and one—Goethe’s Faust—was repeatedly invoked as an ideal tenant.

The story of the House of Government consists of three parts. Book 1, “En Route,” introduces the Old Bolsheviks as young men and women and follows them from one temporary shelter to another as they convert to radical socialism, survive in prison and exile, preach the coming revolution, prevail in the Civil War, build the dictatorship of the proletariat, debate the postponement of socialism, and wonder what to do in the meantime (and whether the dictatorship is, indeed, of the proletariat).

Book 2, “At Home,” describes the return of the revolution as a five-year plan; the building of the House of Government and the rest of the Soviet Union; the division of labor, space, and affection within family apartments; the pleasures and dangers of unsupervised domesticity; the problem of personal mortality before the coming of communism; and the magical world of “happy childhood.”

Book 3, “On Trial,” recounts the purge of the House of Government, the last sacrifice of the Old Bolsheviks, the “mass operations” against hidden heretics, the main differences between loyalty and betrayal, the home life of professional executioners, the long old age of the enemies’ widows, the redemption and apostasy of the Revolution’s children, and the end of Bolshevism as a millenarian faith.

The epilogue unites the book’s three strains by discussing the work of the writer Yuri Trifonov, who grew up in the House of Government and whose fiction transformed it into a setting for Bolshevik family history, a monument to a lost faith, and a treasure of world literature.

■ ■ ■

In the House of Government, some residents were more important than others because of their position within the Party and state bureaucracy, length of service as Old Bolsheviks, or particular accomplishments on the battlefield and the “labor front.” In this book, some characters are more important than others because they made provisions for their own memorialization or because someone else did it in their behalf.

One of the leaders of the Bolshevik takeover in Moscow and chairman of the All-Union Society for Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries, Aleksandr Arosev (Apts. 103 and 104), kept a diary that his sister preserved and one of his daughters published. One of the ideologues of Left Communism and the first head of the Supreme Council of the National Economy, Valerian Osinsky (Apts. 18, 389), maintained a twenty-year correspondence with Anna Shaternikova, who kept his letters and handed them to his daughter, who deposited them in a state archive before writing a book of memoirs, which she posted on the Internet and her daughter later published. The most influential Bolshevik literary critic and Party supervisor of Soviet literature in the 1920s, Aleksandr Voronsky (Apt. 357), wrote several books of memoirs and had a great many essays written about him (including several by his daughter). The director of the Lenin Mausoleum Laboratory, Boris Zbarsky (Apt. 28), immortalized himself by embalming Lenin’s body. His son and colleague, Ilya Zbarsky, took professional care of Lenin’s body and wrote an autobiography memorializing himself and his father. “The Party’s Conscience” and deputy prosecutor general, Aron Solts (Apt. 393), wrote numerous articles about Communist ethics and sheltered his recently divorced niece, who wrote a book about him (and sent the manuscript to an archive). The prosecutor at the Filipp Mironov treason trial in 1919, Ivar Smilga (Apt. 230), was the subject of several interviews given by his daughter Tatiana, who had inherited his gift of eloquence and put a great deal of effort into preserving his memory. The chairman of the Flour Milling Industry Directorate, Boris Ivanov, “the Baker” (Apt. 372), was remembered by many of his House of Government neighbors for his extraordinary generosity.

Lyova Fedotov, the son of the late Central Committee instructor, Fedor Fedotov (Apt. 262), kept a diary and believed that “everything is important for history.” Inna Gaister, the daughter of the deputy people’s commissar of agriculture, Aron Gaister (Apt. 162), published a detailed “family chronicle.” Anatoly Granovsky, the

son of the director of the Berezniki Chemical Plant, Mikhail Granovsky (Apt. 418), defected to the United States and wrote a memoir about his work as a secret agent under the command of Andrei Sverdlov, the son of the first head of the Soviet state and organizer of the Red Terror, Yakov Sverdlov. As a young revolutionary, Yakov Sverdlov wrote several revealing letters to Andrei’s mother, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (Apt. 319), and to his young friend and disciple, Kira Egon-Besser. Both women preserved his letters and wrote memoirs about him. Boris Ivanov, the “Baker,” wrote memoirs about Yakov’s and Klavdia’s life in Siberian exile. Andrei Sverdlov (Apt. 319) helped edit his mother’s memoirs, coauthored three detective stories based on his experience as a secret police official, and was featured in the memoirs of Anna Larina-Bukharina (Apt. 470) as one of her interrogators. After the arrest of the former head of the secret police investigations department, Grigory Moroz (Apt. 39), his wife, Fanni Kreindel, and eldest son, Samuil, were sent to labor camps, and his two younger sons, Vladimir and Aleksandr, to an orphanage. Vladimir kept a diary and wrote several defiant letters that were used as evidence against him (and published by later historians); Samuil wrote his memoirs and sent them to a museum. Eva Levina-Rozengolts, a professional artist and sister of the people’s commissar of foreign trade, Arkady Rozengolts (Apt. 237), spent seven years in exile and produced several graphic cycles dedicated to those who came back and those who did not. The oldest of the Old Bolsheviks, Elena Stasova (Apts. 245, 291), devoted the last ten years of her life to the “rehabilitation” of those who came back and those who did not.

The House of Government

The House of Government